This is the second part of a two-part blog series on the EU’s uncertain future direction in light of Brexit, populism and other challenges. To read the first section, click here.

This is the second part of a two-part blog series on the EU’s uncertain future direction in light of Brexit, populism and other challenges. To read the first section, click here.

In awarding the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize to the European Union, the Nobel Committee “wished to reward the EU’s successful struggle for peace, reconciliation and for democracy and human rights […] in this time of economic and social unrest.” When one considers the tumult of the years since then – the annexation of Crimea, the drowning of tens of thousands of migrants in the Mediterranean, the consolidation of authoritarian populism across Europe and the fraying fabric of western democracy – 2012’s idea of “unrest” seems almost quaint. The EU prevails, however – albeit with the weight of history bearing ever more heavily on its shoulders.

We are all familiar with the EU’s “origin myth” – to make war in Europe not just unthinkable, but materially impossible. It has accomplished this mission so well that many of its citizens appear to have forgotten what purpose it serves; worryingly, it could be argued that the EU has forgotten, too. The goalposts of liberal internationalism have shifted. The EU helped to move them. And although it pays lip service to the maxim of “never again war,” Europe’s institutions have far less to say as regards “what next?”

*

Now is a good time to ask the question, as the EU and its member states are currently finalising negotiations on the next Multi-Annual Financial Framework (MFF), the Union’s budget for the next seven years. What was already a complex diplomatic exercise has been rendered trickier still by the impending withdrawal of the UK and its sizeable budget contribution, as well as the spectre of populism and nationalism which currently overshadows all European politics.

We’ve already seen the British vision of the future at it prepares to leave: a Union of convenience, measured solely by its weight in gold (or gunpowder). And the UK isn’t alone. In this “time of unrest,” the idea of a securitised EU has friends among both federalists and sceptics. For the former, going it alone on military matters is the final frontier of “ever closer union” and a handy insurance policy against American unpredictability; for the latter, security cooperation at home and abroad is the deus ex machina for Europe’s permeable southern border.

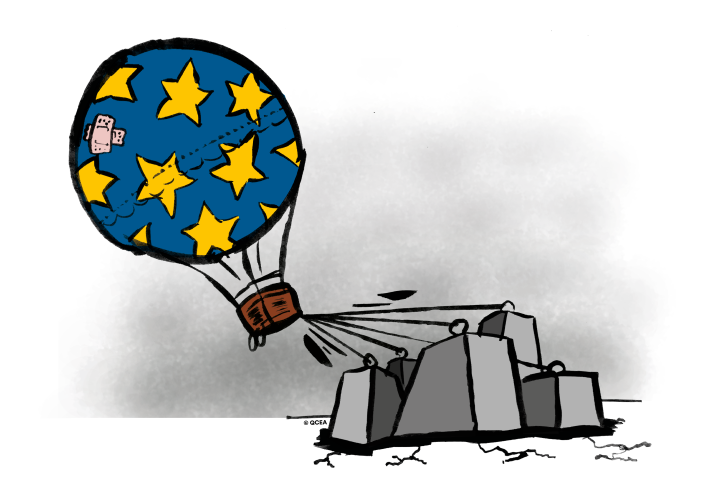

In the last few months, twenty-five EU member states agreed on Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), which devotes €13bn from the Union’s squeezed budget to military cooperation and defence research. More is set to come following the agreement of the MFF, which proposes to subsume vital funding for peacebuilding into a more general pot. In practice, this means that funding for true peace work may be sidelined, just when it’s needed most. And what’s more, these new arrangements would pour further billions into arming and training African armies without any oversight from the European Parliament.

Human rights and development funding fares better in the proposed new budget, rising by approximately 25% compared to the period 2014-2020. But when compared to the plans for a European Border and Coast Guard Agency, a European Union Agency for Asylum and their associated funds, the priority is clearly building walls rather than building bridges. The EU calls it “addressing the root causes of migration,” but among NGOs like QCEA it feels like the ghost of Fortress Europe is simply back to haunt us. Maybe he never went away?

*

It’s easy to read this and despair – wasn’t the EU meant to be about making the world a better place; a spirit of brotherhood? Well, yes. But it’s important to remember two things. Firstly, when the EU was negotiating its last budget and accepting its Peace Prize in Oslo, the world was a different place. Back then, its biggest concern was fiscal stability in the wake of the Eurozone crisis. Brussels has now become the forum for a totally different set of challenges. Which brings us to the second point: we’re all guilty of ascribing too much agency to the EU. We talk about its policies and decisions, its successes and failures, but if anything it’s a mirror for the collective concerns and interests of its members. And many of its members are currently in the grip of xenophobia, populism and nationalism. If the EU is to right its course and embody its founding values once again, national politics – and voters across Europe – must wish it to be so.

The EU is a major player in global affairs, shaping the world we live in by virtue of its size alone. But it is nonetheless a blank canvas, pulled taut in different political directions, on which a myriad of actors seek to chart Europe’s future course. It is up to us all to provide the compass; in Brussels, QCEA aims to show the way.

Interested in how the EU could develop in the years to come, and what the future holds for multilateral cooperation in Europe? Why not join QCEA’s Study Tour to Brussels in March 2019? Click here for more details.

Pingback: On British cherry-picking, and other rotten fruit | The QCEA Blog